by PAUL HOLLIS

Avian influenza—commonly known as bird flu or AIV—has proven to be a serious threat to poultry flocks worldwide, making it all the more important that researchers learn how it spreads to poultry farms.

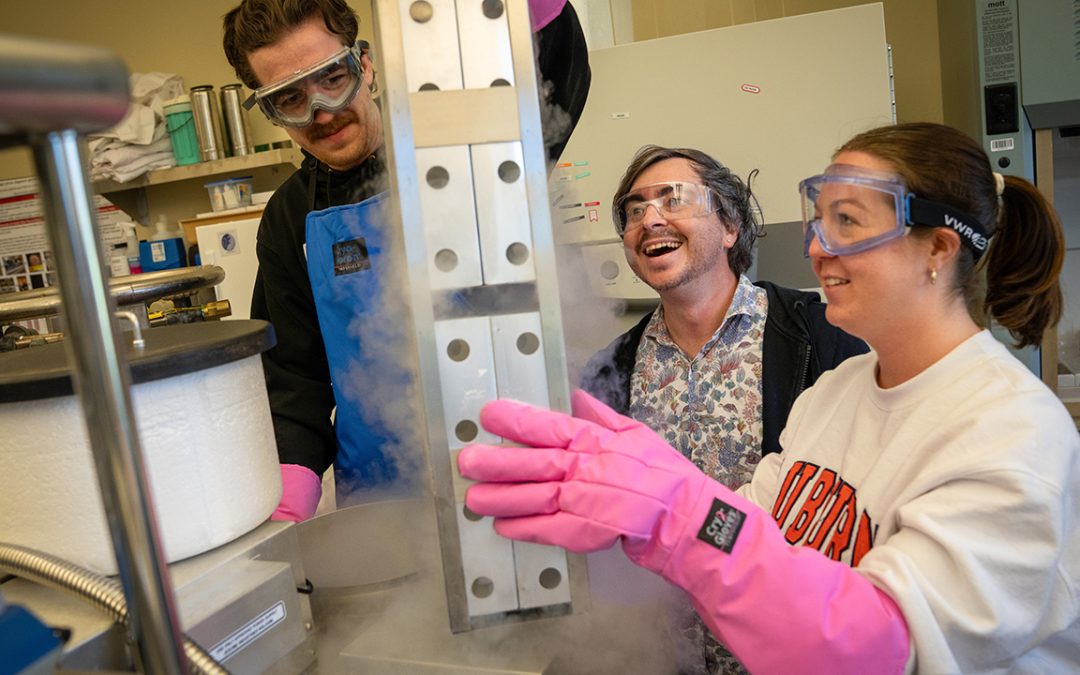

That’s the aim of continuing work by Auburn University poultry scientists Joe Giambrone and Ken Macklin, who are investigating the possible spread of AIV through mice, darkling beetles, poultry feed and poultry house drinking water.

Since 2014, about 50 million poultry in at least 15 states either have been killed by the virus or had to be depopulated due to the presence of the virus. This resulted in a loss of $3.2 billion to the U.S. economy, not only because of the loss of birds but also because many other countries temporarily embargoed U.S. exports.

“For our research, we’re using a virus isolated from hunter-killed ducks in Florida that does not cause disease,” Giambrone said. “We will infect mice and beetles, inoculate the virus onto feed, and put it into poultry drinking water. Then, we’ll see if the virus is stable for any period of time, which can lead to its spread in poultry flocks.”

Completion of the recently begun study—funded by the Iowa-based Egg Industry Center—is about a year and a half away, he said.

“We know some poultry viruses can live in beetles, mice and drinking water for a period of time,” Giambrone said. “This research will determine if our influenza virus is stable in these potential sources, in addition to chicken feed.”

Darkling beetles are commonly found in chicken houses, thriving in warm, moist areas and consuming spilled feed. Chickens love to eat the beetles and their larvae, he said.

Giambrone and Macklin are looking at three water experiments, including inoculating the virus in distilled water, chlorinated city water, unchlorinated groundwater and lake water. Many producers use groundwater sources for poultry drinking water.

“Groundwater enters chicken houses through pipes that can build up with algae and other organic matter, called biofilm,” Giambrone said. “We’re assuming the virus can get into water pipes and survive in the biofilm, which could infect future flocks.”

Even though the house can be cleaned and disinfected, live virus still could be present in drinking water, in beetles buried in the litter, in new feed shipments, and in mice that enter into the house after cleaning, he said.

“At wildlife refuges, it has been shown that wild ducks can get infected, defecate in the water, and then the virus will be present in the lake water, infecting other water fowl,” Giambrone said.

The problem with the virus is two-fold, he said. One, it is spread worldwide by wild free-flying ducks and geese. Two, the virus can recombine and mutate with influenza viruses from other sources including pigs, humans and other animals. These resulting mutated viruses can cause disease within many animal species, including humans.

“Alaska is a common breeding ground for water fowl,” Giambrone said. “There are also wild, free-flying ducks from Europe and Asia that can intermingle with ducks from North America, spreading mutated viruses worldwide. The recent virus that caused disease in much of Canada and the U.S. contained genetic material from birds from all three continents.”

The good news is that the virus is not very stable during the summer months, when ducks have moved north. However, it is almost certain ducks will bring the virus back in the fall, Giambrone said.

“In the fall of 2014, ducks brought this highly mutated disease causing influenza virus into the U.S.,” he said. “It spread quickly because some producers were not practicing strict biosecurity measures. Vaccination is not used here because the virus mutates so quickly.”

U.S. commercial poultry producers now have stringent regulations to examine all commercial and many larger backyard poultry flocks for the presence of the virus, and all producers must practice biosecurity measures.

In less developed countries that do not have this level of detection and security, people have become ill from the virus when buying non-inspected poultry from live bird markets.

“We’re lucky so far that the virus has not been shown to spread among humans,” Giambrone said. “To date, no North American humans have becomes ill due to this virus.”

The Auburn scientists also are working with the Cuban government to determine the presences of AIV in that country’s water fowl.