AU Lean comes full circle

Throughout the 2022-2023 academic year, the College of Agriculture is celebrating its 150th anniversary with content shared from its special edition, collector’s book of The Season, publishing in 2023.

By Mike Jernigan

In an era when “meat” derived entirely from plants has become increasingly mainstream and such products are available everywhere from fast food outlets to your local grocery store, it is worth a look back at the role the Auburn College of Agriculture — and Auburn researchers Dale Huffman and Russ Egbert — played in the early search for a healthier meat alternative, long before the current craze began.

The meat in question at the time was ground beef, the everyman of the meat sciences world, and when the National Livestock and Meat Board sent out a 1987 request for proposals for the development of a light ground beef, Auburn was one of only three universities to respond. The Alabama Cattlemen’s Association also provided funding, and Huffman, a professor in the Department of Animal and Dairy Science, and his research associate, Russ Egbert, set out on a quest to develop a healthier hamburger.

It was a field where little or no work had been done before. In fact, healthier eating in general was not a widespread concern. “Not many people bid on this contract,” said Huffman at the time of the less than overwhelming response to the proposal request. “It’s not very exciting to work with hamburger. Everybody wants to work with T-bone steaks.”

The challenge was considerable, since traditional ground beef can contain as much as 20-30% fat. The more fat removed from the cuts making up the beef, the more bland and dry the final product becomes. The object for Huffman, Egbert and their team was to find a substitute that could replace the fat in order to maintain moistness in the meat, while at the same time mimicking the consistency and taste of a higher fat content.

The search for that perfect substitute took three years, and plenty of burger sampling in the name of science. Egbert was the chief burger chef, and a panel of 18 tasters, consisting of “graduate students, technicians and staff members,” sampled each test patty, eating the good, the bad and the ugly. “Some were bland and dry,” admitted Egbert. “Other than that, most weren’t that objectionable, or at least not anything you’d want to spit out of your mouth.” Huffman was more clinical. “They worked almost like an instrument,” he recalled later. “They were trained; they ate hamburger every day.”

Finally, after trying more burger combinations than most of the tasting panel wanted to remember, Huffman and Egbert hit on what they hoped was a winning formula. Dubbed “AU Lean,” the recipe resembled “ground beef mousse,” according to one contemporary newspaper account, and relied on the use of carrageenan — a seaweed derivative already widely used in the food industry as a thickening agent — to seal in moisture and create the textural consistency of a hot-off-the-grill burger.

Huffman also added more salt as well as beef flavoring, to compensate for the reduction in fat. The extra blast of flavor was intended to convince the mouth it was being bathed in beef fat. Eaten fast, the slightly spongy texture of the patty hopefully went unnoticed. On a burger loaded with condiments and lettuce, onions, most tasters never suspected they were sinking their teeth into anything less than the real thing.

When it was first introduced, AU Lean became an immediate hit — far beyond Huffman and Egbert’s wildest expectations. The biggest customer was McDonald’s, which planned to feature the Auburn-developed ground beef as the centerpiece of a new burger it dubbed the “McLean Deluxe.” The world’s largest hamburger chain was so impressed with the results of the low-fat burger it tested in more than 400 stores that it rushed through its normal years-long testing and development phase for new products.

“It’s been extremely successful,” Huffman was soon telling The Auburn Plainsman. “This is the fastest McDonald’s has ever moved a product through testing to full marketing. It is very indicative of the level of interest and acceptance of the product.” Within four months, the McLean Deluxe — which had 9 grams of fat and 320 calories compared to the chain’s popular Quarter Pounder with 20.7 grams of fat and 410 calories — was available at McDonald’s outlets across the nation. “We like to think of this as the first step in McDonald`s menu of the ’90s,” said Edward H. Rensi, president of McDonald`s U.S.A., at a packed news conference at the company`s Oak Brook, Illinois, headquarters.

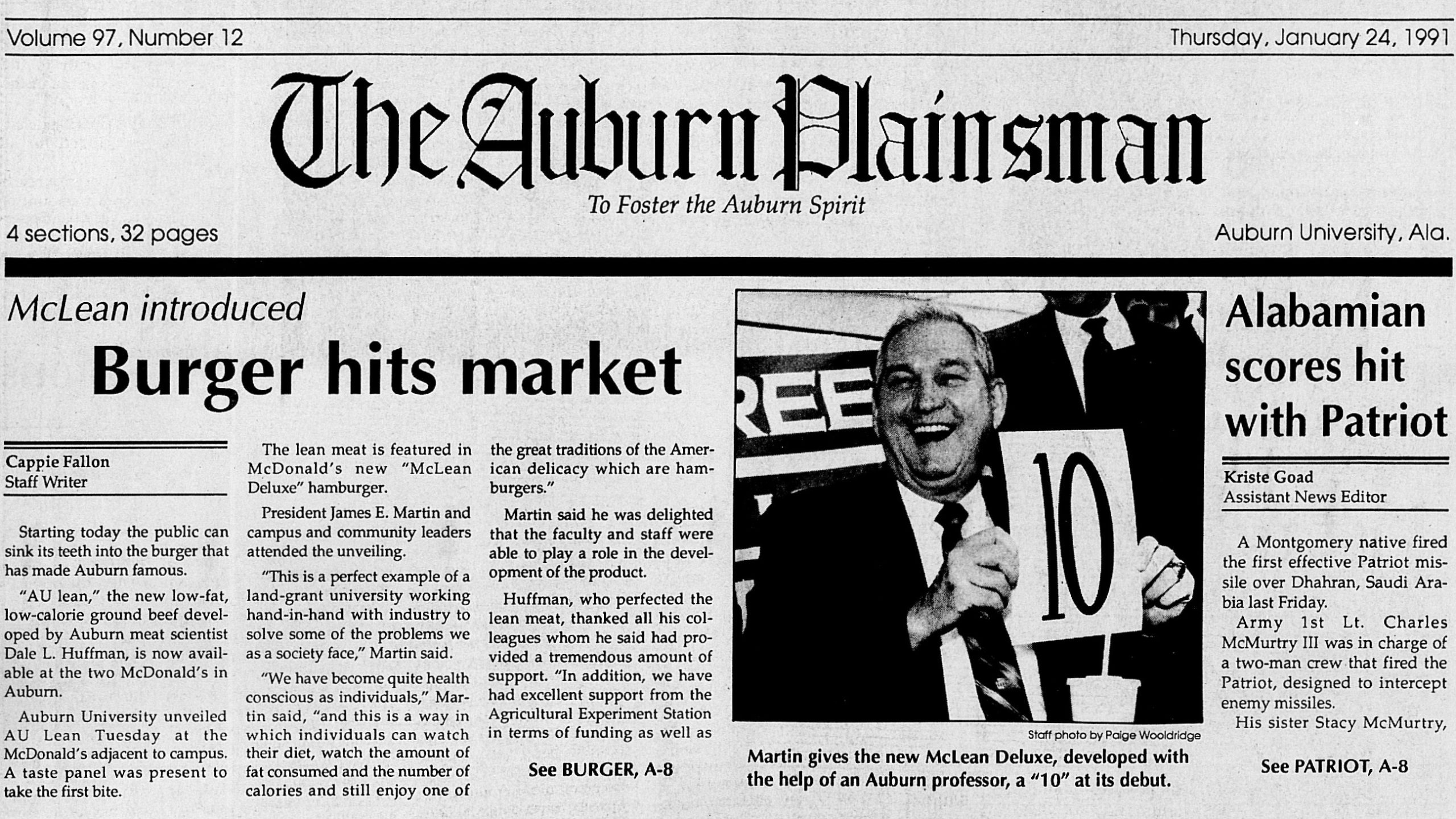

That healthier menu included the Auburn campus. On January 22, 1991, the McLean Deluxe was unveiled at the McDonald’s on Magnolia Avenue. Then-Auburn president Dr. James Martin, who attended along with Miss Auburn Debbie Hunter and SGA president Terry McCarthy, gave the latest and greatest promise of healthy fast food a big thumbs up. Auburn mayor Jan Dempsey even proclaimed it “AU Lean Day” on behalf of the city.

“This is the perfect example of a land-grand university working hand-in-hand with industry to solve some of the problems we face as a society,” a proud Martin said. “We have become quite health conscious as individuals and this is a way for individuals to watch their diet, watch the amount of fat and calories consumed, and still enjoy a great American hamburger.”

With Huffman and Egbert having made their recipe for AU Lean available in the public domain, other customers rushed to follow. Disneyland, Disney World and MGM Studios served it in their restaurants. AU Lean was sold on the retail market in New York. The National School Lunch Program ordered 250,000 pounds to taste test in school meals. Wendy’s and Burger King even got in touch. All the while, McDonald’s was spending an estimated $50 million touting the benefits of the miracle meat in full-page magazine and newspaper ads and in multiple nationwide television commercials. The McLean was even named the official sandwich of the NBA.

But despite its initial success, the McLean Deluxe and AU Lean soon proved to be a burger too far. Maybe they were both ahead of their time. Within two years, McDonald’s great experiment in healthier eating — and AU Lean along with it — were about as popular as stale day-old fries under a heat lamp.

In a 1993 article, the Seattle Times plopped the nation’s brief fascination with low-fat meat alternatives right back into a hot-grease-filled fryer. “As Bill Clinton rolled into Washington, so did a sandwich better suited to his fill-me-up appetite: the ‘Mega Mac.’ It’s the biggest, fattest burger ever to come off a McDonald’s grill — a half-pound monument of ground beef slathered with sauce, sprinkled with lettuce and onions and stuffed into the same three-piece bun that holds its puny patriarch, the Big Mac.

“Many people seem to be putting good taste before good nutrition again, and that means f-a-t,” the newspaper continued. “Supermarket freezer cases feature large-portion dinners, and ‘hearty’ has replaced ‘healthy’ as the hot word on new foods. Bacon sales rose four percent last year. Meanwhile, the flurry of fake fats designed to slim down the nation’s waistline has quietly faded.” During the summer of 1996, just five years after its spectacular introduction, the McLean Deluxe was quietly removed from the menus of the last few McDonald’s still offering it. With it went the last major market for AU Lean.

In a 2012 article, The War Eagle Reader theorized about the McLean Deluxe’s rapid fall from grace. “Maybe it was the absence of the familiar flavor and ‘mouth feel’ (the decreased fat apparently made it dryer than normal burgers), or the price (they were the most expensive item on the menu) or the two-minute wait (they had to be made to order). Whatever the reason, the McLean Deluxe never McDid it for America. Billions and billions of them were not served. What The New York Times had initially heralded as ‘a healthy breakthrough for the American public’ was soon being called the McFlopper.”

But whatever else can be said about the marketing failure of the McLean Deluxe, there is no denying that in the long run, the Auburn-developed AU Lean it was made from was a success. Huffman and Egbert’s creation laid important scientific groundwork for the lower-fat meat alternatives that are enjoying a Renaissance today. In addition to showing it was possible to develop healthier meat products, their use of the seaweed derivative carrageenan as a binder and fat substitute in AU Lean was an early precursor of the use of heme — an essential molecule found in both plants and animals and produced via fermentation of genetically engineered yeast — in current totally plant-based meat substitutes.

Today, with heme-based meat substitutes widely available and gaining growing acceptance among the nation’s consumers, it has become increasingly apparent that Huffman and Egbert were major pioneers in the field. Their early work with low-fat ground beef has come full circle — as round as a fast-food hamburger patty in fact. In the end, it’s fair to say that thanks to the impact of their research on modern meat alternatives, perhaps AU Lean really McDid it after all.