API shifts focus in ‘40s to support war-driven priorities

THROUGHOUT THE 2022-2023 ACADEMIC YEAR, THE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE IS CELEBRATING ITS 150TH ANNIVERSARY WITH CONTENT SHARED FROM ITS SPECIAL EDITION COLLECTOR’S BOOK OF THE SEASON, PUBLISHING IN 2023.

Imagine it.

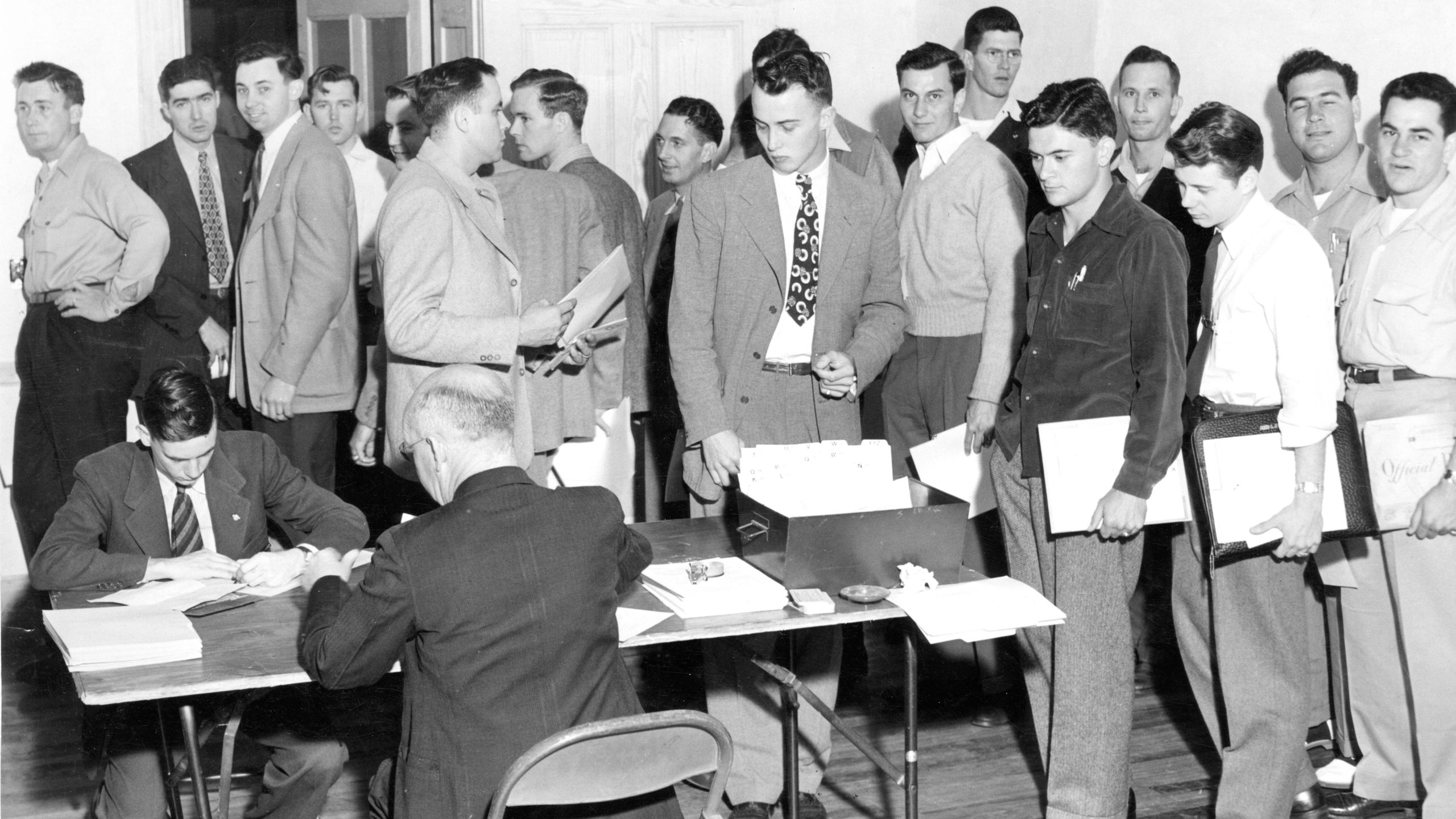

You’re 21 years old, and you’ve been told to report to the basement of Samford Hall.

You’re going to war.

On Dec. 12, 1941 — five days after the Japanese military surprise attack on the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii — registered male students at Alabama Polytechnic Institute who were 21 and older dutifully assembled in said basement and provided information on their status in Selective Service. Within a week, 15 of them were already gone.

In the early stages of the war, college students were deferred. The ROTC programs on campuses like API’s were vital for supplying commissioned officers during World War II. By the end of the 1942 academic year, 169 ROTC graduates commissioned.

API President Luther Duncan wrote to the board in June 1942, “The impact of war has had its effect upon the Alabama Polytechnic Institute during the past year, as it has on all institutions and activities of the country.”

By 1943, the advanced ROTC course closed, and the U.S. Army ordered all advanced cadets to active duty. Seniors went to officers’ candidate schools and juniors to replacement training centers. During the academic year, nearly 1,500 students joined reserve units and by July of that year, Selective Service drafted all male students over 18 years of age who were not already on active duty.

That year, Duncan wrote, “We believe that no other college in the country, other than the Naval and Military Academies, has contributed a larger percentage of officers to the armed forces…. [But] We have been saddened at the cost in courageous young Auburn men which the war has thus far extracted.”

One such courageous young man was Ambers Hanson.

A World War II veteran who completed 25 bombing missions before turning 21, Ambers grew up in Ranburne, Alabama, and would help his family farm their land and care for their livestock.

When the war came, he joined the U.S. Army Air Corp.

“They sent me to radio operator school in Illinois,” he said. “And that was my job when we were flying; I was the radio operator.”

He was stationed in Mendlesham, England through the war, flying missions in France, Germany and what was then Czechoslovakia as a member of the 34th Bombardment Group, 391st Bomb Squadron. He flew 25 combat missions as a young man who had not yet finished high school.

“Flew through a lot of flak and explosions,” he said. “Do you know what flak is? We’re flying at, oh say, something like 25,000 feet. At that time, that was way the heck up there. The big guns the Germans had would shoot this stuff up there, and when it got to our elevation, shrapnel went everywhere in a cloud of black smoke. That’s flak.

“I’d just pray that it wouldn’t hit me.”

Ambers has a large collection of well-preserved paraphernalia from the war, from photographs of himself and his B-17 “Battlin’ Butch,” to a certificate of honor listing all the places his group bombed. He even has the silk scarf printed with a map that was given to each of them before deployment.

“All of the crew members had one,” Ambers said. “It was made out of silk so it couldn’t be destroyed by wetness. If we crashed or bailed out, if anyone was able to escape, then we had a map and might be able to find ourselves a way out.”

Meanwhile, researchers in Auburn were engaged in projects requested by the nation’s War Department.

Station entomologists conducted pest control studies which aided in the fight against lice, ants, roaches, flies, and mosquitos plaguing Southern military camps. Agronomists distributed three varieties of nitrogen-fixing vetches tested by the Station to reduce domestic farmers’ dependence on nitrogenous fertilizers. This allowed greater quantities of nitrogen to be used by the military for explosives.

Perhaps the most ambitious military-related project was a cooperative one between the station’s agricultural engineers, led by Fred A. Kummer, and the United States Army Ordnance personnel using the USDA tillage research facilities that were built in 1935. In three years of study beginning in 1942, researchers determined that the track or tread design on military vehicles greatly affected traction on different types of soils. Not only did this project contribute to better tread designs for military vehicles — and, by extension, for farm vehicles — it also suggested the need for “soil reconnaissance” as part of strategic planning.

Shortage of labor was one war-related problem faced at departmental field or farm units. One year, the College Dairy got along with only the manager and one laborer to do all the milking by hand, feed mixing and all other chores associated with running a dairy. And the beef cattle and dairy units got by for several years with the use of 30 German prisoners of war from the POW camp at Opelika.

During the war, Agricultural Engineering Professor J. H. Neal kept his boys informed with regular newsletters in which he would share college news with the young men stationed across the world and disseminate news they sent to him.

One such newsletter, dated Aug. 31, 1944, shared news both cheerful and tragic. He tells of plans for the college’s new arboretum, “which is to be west of the president’s mansion,” alongside the news that “Lt. Albert Thomas, son of Professor Thomas in the Engineering Drawing Department, is a prisoner of war in Germany.”

A “Captain Johnson” shared with Neal his experiences stationed in Italy. “He said he knew the Italians had good grain and vegetable crops,” Neal said, “because he sampled them as he marched through their fields.”

And while many of Auburn’s men entered the armed forces as volunteers or draftees, Auburn women also stepped up during the war.

Those with experiences in extension work and education volunteered for the women’s corps as U.S. Navy “WAVES” or U.S. Army “WACS” to direct food services or social canteens, or to administer USO operations.

And in 1942 the Alabama Farmer wrote of “tractorettes,” which it defined as “farm girls or women who want to help with the battle of the land, to help provide food for freedom.”

By 1944, for the first time in the institute’s history, women outnumbered men as regular students at Auburn.

As Duncan wrote in June of that year, “Such are the demands of war.”

When the war ended, students like Hanson came back home to find the nation a different place.

Hanson knew how to plow a mule, a method that had gone by the wayside while he was busy fighting for his country. He didn’t have a high school diploma, but he was also 21 years old.

“I went back to high school, and the principal and some of the teachers decided I didn’t need to be there,” he said. “The principal suggested that I come to Auburn.”

He worked a couple of odd jobs in Anniston before deciding to enroll at West Georgia College in Carrollton, Georgia. He took classes there for over a year before transferring to the College of Agriculture at API, where he majored in agricultural science.

By mid-1944, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, more commonly known as the GI Bill of Rights, passed Congress; planning for the returning veterans began in earnest. The Association of Land-Grant Colleges and Universities wrote a report on postwar planning, the Selective Service System converted from drafting men to assisting returning veterans, and API developed new programs and curricula for veterans.

In a 1954 speech from Duncan’s successor, API President Ralph Brown Draughon lauded the “magnificent services” of API during the war and the thousands of students who served with distinction in the Armed Forces.

“Many won honors for services beyond the call of duty,” Draughon said. “Many, too many, gave their lives. They were the true War Eagles, and wherever they served, men learned of the Auburn Spirit and heard their battle cry.”