Agriculture at API helped bring light to farmers

THROUGHOUT THE 2022-2023 ACADEMIC YEAR, THE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE IS CELEBRATING ITS 150TH ANNIVERSARY WITH CONTENT SHARED FROM ITS SPECIAL EDITION COLLECTOR’S BOOK OF THE SEASON, PUBLISHING IN 2023.

It seems strange to think about now, in an era when electricity powers so many things in our modern lives — from smartphones and computers to increasing numbers of automobiles — but the idea of electrical power was not always greeted with enthusiasm. In fact, in the 1920s, as electrification became increasingly common in Alabama’s cities and towns, many of the state’s farmers and rural residents viewed this new-fangled technology with outright suspicion, if not open hostility.

Light from an oil lantern, water from a bucket raised from a hand-cranked well, and cooking and heat from a wood or coal-fired stove had been good enough for generations of rural families, and a change from these traditions didn’t come easily to Alabama farmers whose primary concern was putting food on the table in tough economic times. To make matters worse, the boll weevil was ravaging the state’s traditional cash crop, and many farmers were already overwhelmed by the necessity of switching to other crops and away from King Cotton. It wasn’t an ideal time for more upset in their lives.

They had to be convinced electricity would make their lives easier and their farms more profitable. And, as they had with convincing them crop rotation would help them overcome the boll weevil, the College of Agriculture at Alabama Polytechnic Institute, along with the Agricultural Experiment Station and the Agricultural Extension Service, would play a major role in advancing rural electrification in Alabama, this time in partnership with a young company called Alabama Power.

Alabama Power Company had been incorporated in Gadsden in 1906, but like many other small utilities founded just after the turn of the century, it had to build its business literally from scratch. According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, “At the beginning of the 20th century, Alabama was an agricultural state with little electricity-generating capacity and no transmission system. Some Alabama cities and towns generated a small amount of electricity from isolated, mostly coal-fired dynamos that operated street lights, occasional street cars, and some residential lighting. A few industries had generators for lights or motors.”

Over the next few decades, the new company began to buy up other small utilities and build hydroelectric dams to increase its own generating capacity. It also began to market electrical appliances to use that capacity, such as stoves and refrigerators as well as the new “smoothing iron,” designed to make life easier and more convenient. As a result, electrical power gradually expanded in many of the state’s urban areas.

Alabama Power also began to aggressively recruit new industry that would utilize its product, even purchasing and operating in Anniston the first electrical furnace in the South used for the manufacture of steel. But despite these efforts, Alabama remained overwhelmingly rural, and Alabama Power President Thomas W. Martin knew the company had to expand its services outside the cities if it wanted to continue to grow statewide. In 1920, the company built its first rural distribution line in Madison County in northeastern Alabama, serving 10 farms and a cotton gin. The line was only the second in the nation classified as rural, but Martin wasn’t through.

According to Leah Rawls Atkins’ history of Alabama Power, Developed for the Service of Alabama, “Martin knew that electricity could make a world of difference in the lives of Alabama farm families. [But] Education was needed to show farmers the potential of electricity on the farm. Electric motors could pump water from wells for indoor plumbing, and electric hot water heaters were much better than hot water poured from a kettle off a wood-burning stove….”

But how to get that message out to the state’s farmers? Who did they trust? Martin found the answer to his questions — and fellow converts with the same missionary zeal about the potential of rural electrification — in the College of Agriculture at Alabama Polytechnic Institute. In addition, the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station at Auburn had been conducting research aimed at improving agricultural productivity since 1883, while the Alabama Extension Service had been providing outreach and information to farmers through a system of county agents since its founding in 1915. In the college and those two organizations, Martin saw the perfect partners in proving to the state’s rural population that electricity could change their lives for the better. He was frequently quoted as saying “we want to make agriculture a business rather than just a mode of living.”

In 1922, Alabama Power began discussions with three API faculty members who would become instrumental in aiding the company’s efforts to expand its network into the hinterland. They included Marion J. Funchess, who would later become director of the Agricultural Experiment Station; Mark L. Nichols, head of the Department of Agricultural Engineering; and C. D. Miller, an associate professor of agricultural engineering. Martin wanted the trio to suggest ways to utilize the API-based network to reach farmers, and in December of the following year, Alabama Power provided $24,000 to the college to fund research “to determine the value of rural electrification to farmers.” The API Board of Trustees gave its approval to the project in January 1924.

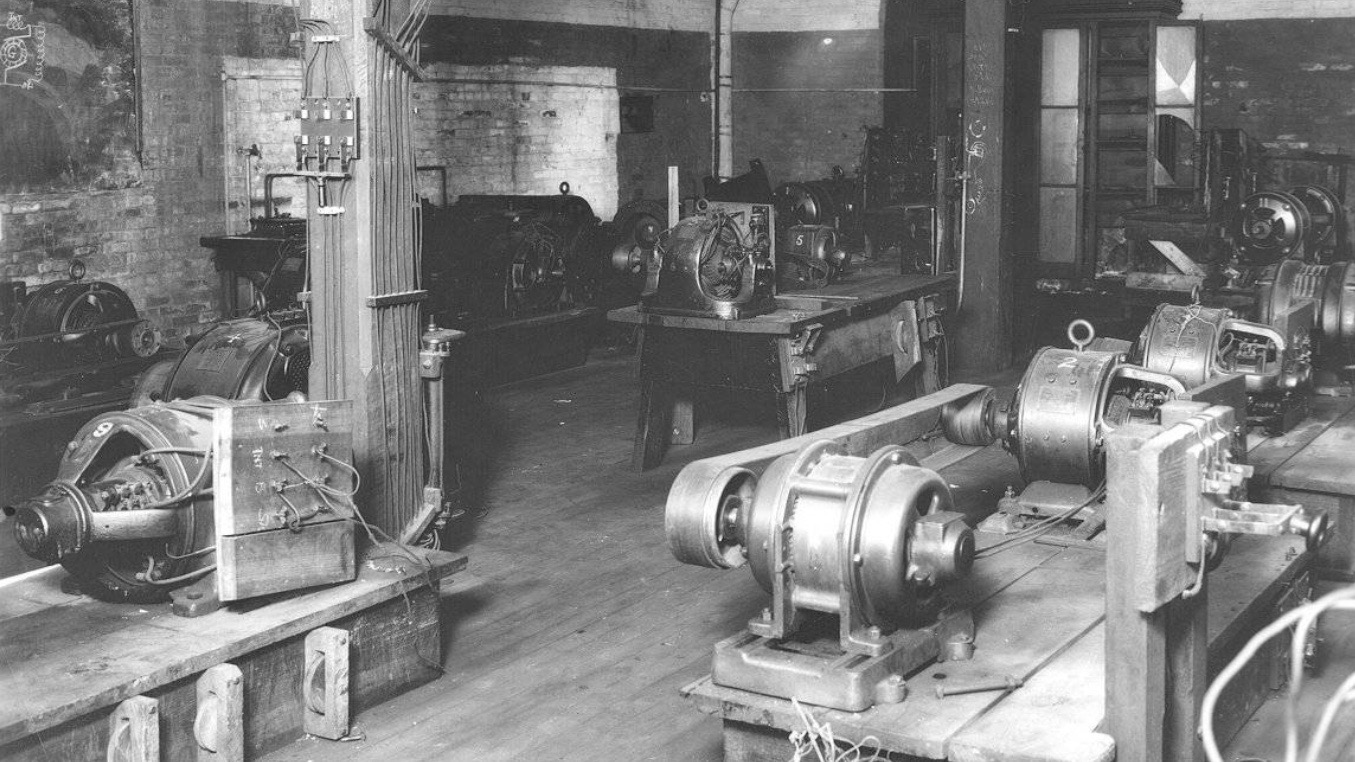

The backbone of the study included electrification of the Agricultural Experiment Station farm in Auburn, a project overseen by Agricultural Engineering Professor E. C. Easter. Accordingly, transmission lines were run, electrical equipment provided by Alabama Power was installed and detailed records were kept of its use and results. One such example was a report on the use of electrical refrigeration for dairy production, authored by Easter and Nichols in 1934.

In a second component of the research, Alabama Power ran three experimental transmission lines into different rural areas of the state, so results could be closely monitored by the API team. The company asked that the researchers pay special attention to “community utilization by schools and churches and to applications such as refrigeration.” Another benefit for the company was the use of home demonstration agents to provide local demonstrations of new electrical appliances marketed by Alabama Power, including the “smoothing iron” and washing machine.

As the first public-private partnership in the U.S. between an electrical utility and a university, the research garnered nationwide attention. The director of the National Committee on the Relation of Electricity to Agriculture called it “the biggest experiment in the world in the economic use of electricity by agriculture.” API President Spright Dowell was even more effusive, saying the research was among “the most important projects undertaken by the Experiment Station. We want to determine how the 256,000 farmers in Alabama, as well as those in other states, can receive the benefits of the use of electricity now enjoyed by city dwellers. It places Alabama in the front rank among the states of the union in work of this kind.”

The Alabama Farm Bureau Federation also took a strong interest in the project, appointing a statewide committee of farmers and agricultural experts to provide input and make suggestions to ensure the research addressed practical concerns. In 1926, the same year API researchers announced their initial overwhelmingly positive findings at the Southern Rural Electrification Conference in Montgomery — attended by land-grant college representatives and industry professionals from across the region — Farm Bureau President E. A. O’Neal noted that, in his opinion, “electricity was reducing farm household drudgery, helping to meet the farm labor shortage and curtailing farm costs to such an extent as to make rural life ideal.”

Thanks to the API studies and continued aggressive expansion outside urban areas by Alabama Power, which also provided electricity to a number of small rural cooperatives around the state, it was soon apparent electrical power had come to Alabama farms to stay. In 1935, when the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) was formed as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to assist in providing electrical power to America’s rural population, Alabama was looked to as already being one of the nation’s leaders.

In fact, the partnership between API — later Auburn University — and Alabama Power continued in one form or another for more than 50 years. One result that was by 1951, just 27 years after the studies got underway, the company had constructed 22,103 miles of electrical lines serving 135,999 rural customers. More than 98 percent of the farms within the company’s service area had been provided with electrical service.

Today, in part thanks to the work conducted by the API Department of Agricultural Engineering, the Agricultural Experiment Station and the Alabama Extension Service in conjunction with Alabama Power Company, it is just as unthinkable for rural areas to be without electrical power as it is for entire cities to be in the dark. Their forward-thinking, first-of-its-kind partnership helped shine a light on the potential of electrical power for all Alabamians.